Hommage panoramique à Julien FREUND (1921-1993)

Maître Jean-Louis Feuerbach

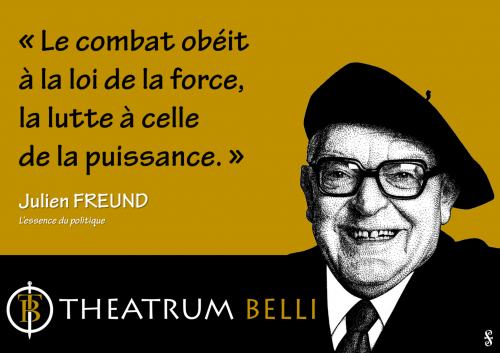

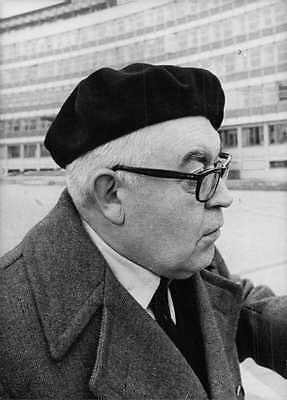

Il y a un siècle, le 09/01/1921, naissait à HENRIDORFF en Moselle, Julien FREUND, grand penseur européen du 20ème siècle.

Avec ses baccalauréats en poche à 16 ans, il enseigne dès l’âge de 17 ans, pour subvenir aux besoins familiaux suite au décès prématuré de son père. Il fut professeur jusqu’à son départ à la retraite en 1988.

La sociologie fut son poste d’observation à l’Université de STRASBOURG II, la philosophie sa culture, la métaphysique sa méthode de hiérarchisation génétique. Il se définira lui-même comme spéculateur, celui qui observe (speculare) puis tisse les liens entre faits et vérité. Enfin, sous-pèse théorie et volonté.

Pour Julien FREUND penser signifie distinguer, comparer, hiérarchiser, séparer, réunir, classer. L’objectivité sera la condition de sa liberté. Aussi son œuvre est-elle, à la fois, recueil de saveurs, d’expériences, d’exemples et d’exposés de sa méthode.

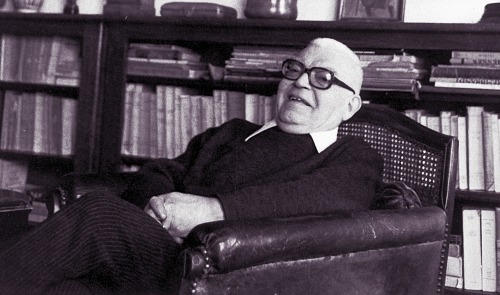

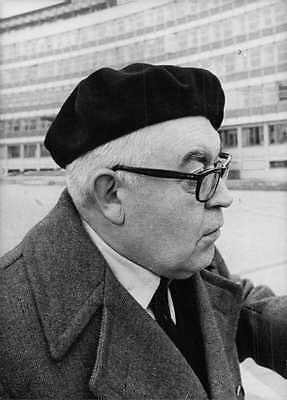

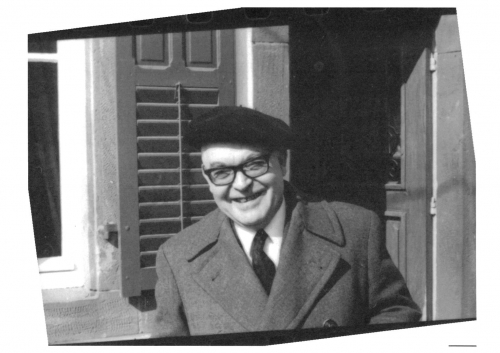

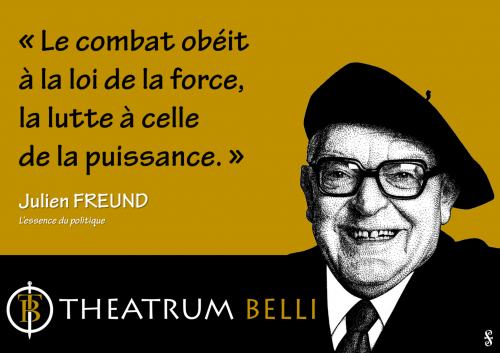

Retiré dans son pagus de Villé, il y méditera, pensera et forgera ses concepts et théories et c’est là également que d’aucuns puissants viendront consulter le sage. Julien FREUND est une pointure hors classe. Sous son béret confluent le savant, le professeur, le résistant.

Dans le bourg de Villé...

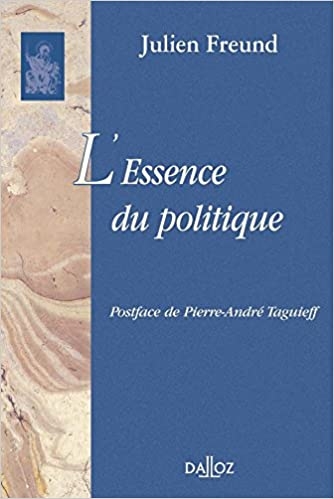

Julien FREUND n’est pas un idéologue mais un théoricien de tout premier plan. Figure de proue du penser de l’inouï et du toujours là, il laissera à son décès le 10/09/1993 une œuvre gigantesque. Ses livres, ses articles, ses communications, ses interventions, ses préfaces, interviews ou traductions sont autant de briques de sa monumentalité. S’y ajoutent les rencontres, à table ou hors de table, les correspondances et malheureusement les travaux égarés, les inédits ou esquisses inachevées.

Discrètement, Julien FREUND n’aura fabriqué que des œuvres et des disciples. Ennemi farouche de la flatterie, il ne recherchera ni courtisans, ni dévots. Il croisera le fer avec le conflit, la violence, l’ennemi, la politicoclastie, la peur de la peur, les diasporismes, psychogogie et sociogogie ou la bêtise des suralimentés.

Il n’aura jamais d’opinion toute faite, se refusant de penser dans les catégories de droite et de gauche qui ne sont que suivisme et mimétisme servile des idées dominantes. Sa science était l’analyse comme recherche de vérité en tout et chez tous en se vainquant lui-même.

Il plantera ses crocs dans toutes les formes du savoir, toutes les formes du réel et de ses représentations, toutes les niches du vivant.

Ses théories sont production d’un amoureux du cœur politique, de la cité et des siens. Il s’agit de les défendre à l’aune du primat de l’amitié politique : BlutFREUNDschaft. Foi de gergoviote !

Le maître fera de la sociologie une science régénérée par la polémologie et n’aura de cesse que de désinfecter les concepts dénaturés. Sa lutte grandiose contre l’utopie sous toutes ses splendeurs fait la matière de son œuvre.

Voici quelques maximes de Julien FREUND à méditer :

- L’humeur est le quotidien de l’être,

- L’égalité est mise en hiérarchie de l’inférieur,

- Le privé est le lieu de nos libres choix,

- L’intellectuel est celui qui vit dans des catégories autres que celles dans lesquelles il pense,

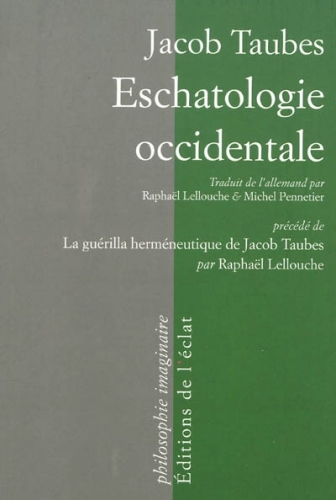

- L’idéologie est une eschatologie sécularisée,

- L’homme politique est moral quand il est au service de la protection effective des citoyens,

- Tout politiser est impolitique,

- L’injustice ne consiste pas seulement à prendre plus que sa part mais aussi moins que sa part,

- Un Etat mondial sera nécessairement un état policier,

- La technique est serve,

- L’économique se ramène à la satisfaction des besoins,

- C’est l’ennemi qui vous désigne.

- Identité signifie fidélité à soi-même.

- Quand tout se vaut rien ne vaut.

- La barbarie est la seule issue de l’idéologie du progrès.

En ces temps freundiens de coïncidence des catastrophes, cinq thèmes saillants de son œuvre peuvent être évoqués :

- Le souci du Nomos (I),

- Le paradoxe des conséquences (II),

- Le rôle du tiers et du 3 (III),

- La lutte contre la décadence (IV),

- L’actualité de sa leçon (V).

Au final, Julien FREUND se rend éligible au rang de classique (VI).

I/ la théorie des essences et des instances.

Le 20ème siècle aura été le siècle des méthodes et non des doctrines. (La mise en agenda est encore plus patente au XXIème siècle). S’affrontent, dès lors, non des idées mais des systèmes.

Julien FREUND disqualifie nazisme et communisme en phases préparatoires du totalitarisme de l’utopie. Il insupporte l’intolérable. Aussi, invente-t-il une théorie englobante du vécu des peuples comme acte constitutif de la contestation du projet collectif des idéologies mondiales. Il les dénonce comme sécularisation des monothéismes.

Julien FREUND disqualifie nazisme et communisme en phases préparatoires du totalitarisme de l’utopie. Il insupporte l’intolérable. Aussi, invente-t-il une théorie englobante du vécu des peuples comme acte constitutif de la contestation du projet collectif des idéologies mondiales. Il les dénonce comme sécularisation des monothéismes.

Sa théorie affronte directement et immédiatement le messianisme des engeances de domination, leurs violences, leur impérialisme. Elle est fondamentalement pharmacopée contre la peur de la peur, la contrainte psychique (hiérocraties), la terreur, la décadence. Sa composition est recomposition des activités des peuples, convoquant données, moyens et finalités pour les identifier comme impératifs (Il y a des libertés et non une liberté ; il y a des droits et non pas un droit ; il y a des histoires et non pas une histoire ; il y a des égalités et non pas une égalité) et déterminismes historiques.

Julien FREUND aura ainsi débusqué des constantes fortes, catégorielles et vitales dans les champs d’activité de l’expérience. C’est ce qu’il qualifie d’essences. Elles sont au nombre de 6 et rien que 6 : l’économique, l’esthétique, l’éthique, le politique, le religieux et le scientifique. Chaque essence a pour fondement une donnée, repose sur des couples de critères appelés présupposés (est un présupposé la condition d’exercice d’une activité comme condition constitutive, à défaut, elle ne pourrait se développer selon sa logique propre et sa finalité), poursuit une fin exclusive.

Pour Julien FREUND :

Les données ou fondements sont : l’économique qui a pour assise le besoin, l’esthétique qui procède du goût, l’éthique qui est le fait d’habiter un lieu, une maisonnée (ethos) en amis, le politique qui a pour cause le peuple politique, le religieux qui a pour fondement la mort, le scientifique qui vise la connaissance dans toutes les acceptions du terme.

Les présupposés ou critères, principes, structures opérant en couples sont : l’économique qui articule rareté et abondance, l’utile et le nuisible, le lien du maître et de l’esclave ; l’esthétique qui convoque la matière et le style, le plaisant et le fastidieux, la mise en relation de l’œuvre et des tiers ; l’éthique qui met en relation tradition et innovation, le convenable et la décence dans le commerce aimable et l’amitié aux personnes et aux choses ; le politique qui est constitutif des relations de commandement et d’obéissance, de séparation du privé et du public et de distinction de l’ami et de l’ennemi ; le religieux qui présuppose la distinction du sacré et du profane, du transcendant et de l’immanent ; la science qui intègre la relation entre quantité et qualité, nécessité et hasard, objectivité et subjectivité.

Le présupposé se signale en ce qu’il polarise son opposé. Il fixe les limites entre lesquelles oscille le réel de la vie.

Le présupposé se signale en ce qu’il polarise son opposé. Il fixe les limites entre lesquelles oscille le réel de la vie.

Les finalités spécifiques de chaque essence sont : que l’économique poursuit le bien-vivre et le bien-être comme résultat de la satisfaction des besoins ; que l’esthétique est art du beau ; que l’éthique poursuit la manière d’être dans l’accomplissement du bien, du bien-faire, de l’habiter (ensemble) sous le toit de la maisonnée commune ; que le politique protège ses ressortissants par la concorde intérieure et la sécurité extérieure, (il est au service du peuple-politique pour garantir aux autres essences la possibilité de se développer, il doit le salut) ; que le religieux a pour finalité la quête de l’absolu et le salut individuel ; que le scientifique poursuit la recherche indéfinie et collecte l’accumulation de la connaissance pour elle-même, son but étant l’intelligibilité du réel. Chaque activité connaît un nombre variable de superstructures d’instances ou dialectiques, telles que le culturel, le pédagogique, le juridique, le social, le technique ou la politique. Chaque essence a une finalité de fonction élémentaire et exclusive. Elle est une réalité qui dure à travers le temps et qui ne disparaît pas sous l’action des circonstances. Elle fait l’histoire et est donc ineffaçable. Julien FREUND invite au strict respect du principe de distinction des essences et des instances. Il n’a de cesse de faire défense que l’une d’elle puisse accomplir l’office de l’autre : chacune étant spécifique, elles ne peuvent être réduites à l’une d’elle. Toute activité s’entend selon ses présupposés et non à partir de ceux d’une ou des autres.

L’empiètement d’une ou plusieurs essences, d’une ou plusieurs instances sur une ou plusieurs autres signe le passage à l’ère de la dévastation totalitaire.

Il stigmatise l’action oblique de l’économisme ou comment faire croire que l’enrichissement de quelques-uns ferait ruisseler la satisfaction des besoins de tous les autres. (Cujus economia ejus regio).

Si toute activité est aux prises avec des contradictions et doit les résoudre avec ses propres moyens, chaque activité ne peut résoudre que les siennes propres. Aucune ne peut et ne doit être la solution aux difficultés des autres. Nul ne saurait régler par les voies du politique des litiges portant sur des questions extrapolitiques, l’économique par la science, l’art par l’éthique… La science n’est compétente que dans les limites de ses présupposées. Hors de là elle n’est que petite science, pseudo-science ou simulacre de science. Il n’appartient pas à la science de définir le beau et le laid.

La concorde n’a lieu qu’au prix du politico-politique, de l’économique à l’économique, etc… Est donc totalitaire qui use de l’autorité politique pour intervenir arbitrairement hors de sa juridiction.

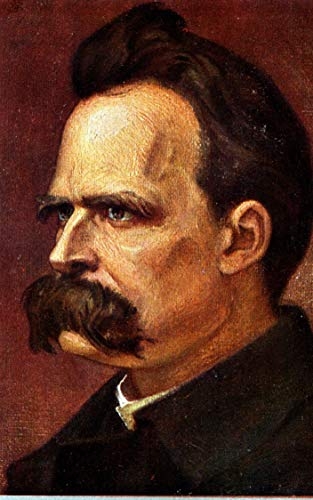

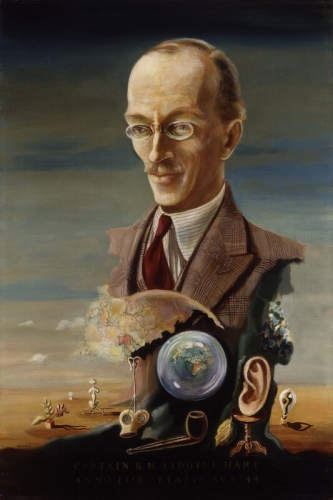

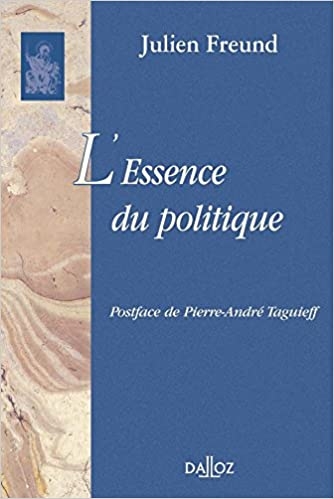

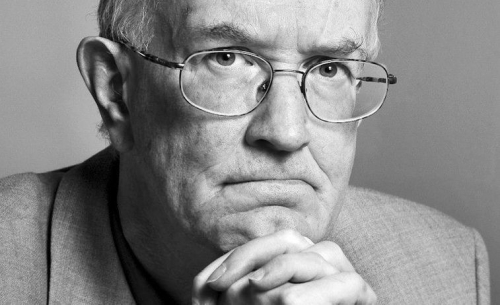

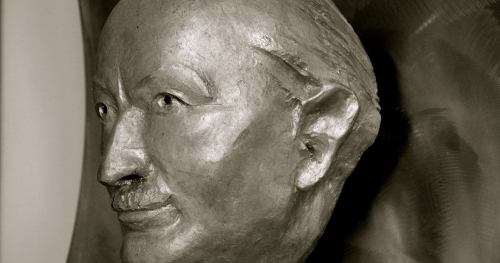

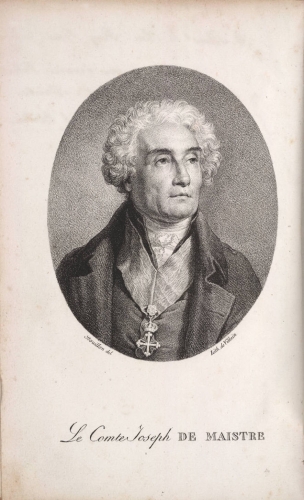

Julien Freund vu par l'artiste alsacien Jean-François Klotz.

Julien FREUND sait qu’aucune activité n’est angélique et que l’économie n’échappe pas à cette loi.

La théorie permet de qualifier déontologiquement ce qui est politique, économique ou autre dans tout phénomène ou de le disqualifier en tant qu’il ne l’est pas et serait autre chose.

La théorie permet enfin des reclassements fulgurants : Les monothéismes sont-ils des religions ou des programmes politiques, économiques ou sociaux ? Le capitalisme ou les droits de l’homme ne seraient-ils pas des religions ?

Par-delà cette grille de structuration anthropologique, Julien FREUND nous propose un système complet de fonctions cardinales polarisées.

Ce système fait socle de contre-création et mathématise un projet d’ordre. Un nomos en puissance.

C’est en ce sens que Julien FREUND est, à la fois, original et inégalable.

Il propose sa théorie à des fins pratiques pour entraîner à l’action.

Tout ce qui existe est formes et mise en forme. Sa création est œuvre d’art mise en état et architectonie politique mais où le tout n’est pas que politique. En termes heideggeriens la formule se ramène au il-y-a-de-l’être-là-avecque et pour.

Reste que le jeu dialectique qui fait l’histoire établit une hiérarchie entre les diverses activités.

Julien FREUND n’a pas eu le temps de solutionner ni la question de la hiérarchie des essences ni de la mise en couple desdites essences. Ne se pourrait-il pas que les essences de l’art, de la religion, du politique et de l’éthique recouvrent la 1ère fonction, le militaire, le technique, le technologique et le scientifique cohabitent au sein de la 2ème fonction tandis que l’économique, subsidiairement l’économie serait le champ de la 3ème fonction ?

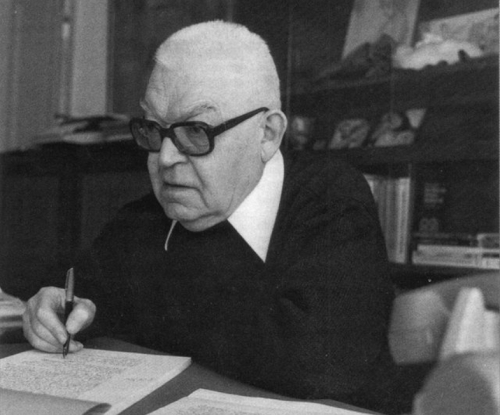

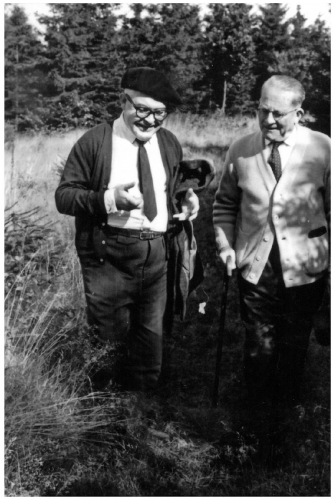

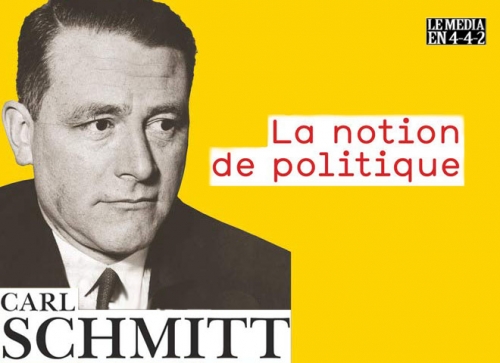

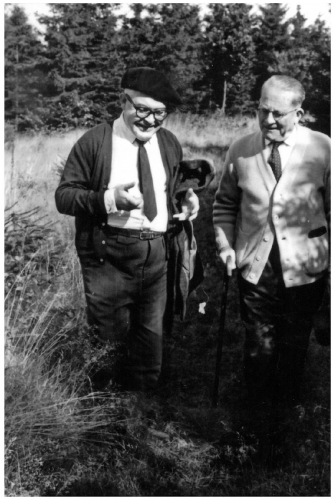

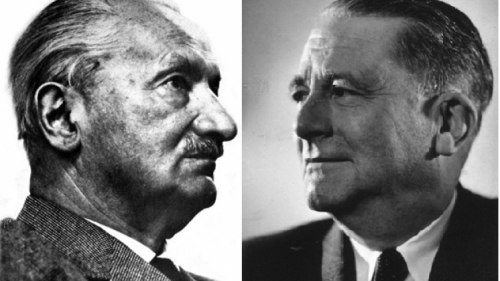

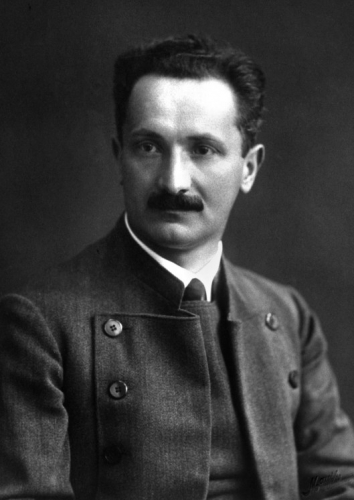

Julien Freund en conversation avec Carl Schmitt.

II/ LE PARADOXE DES CONSEQUENCES

Julien FREUND a identifié un fait fondamental de l’histoire.

L’intention originelle de toute action ou entreprise ne se retrouve pas dans le résultat final. A l’expérience dit-il, le résultat de nos actions est rarement conforme à l’intention ou aux espoirs de départ, pour ne pas dire jamais. Les meilleures intentions peuvent entraîner des conséquences désagréables pour l’auteur et fâcheuses pour les tiers. Nul n’est donc chef des effets de ses décisions.

Il est des projets qui s’abîment en leur contraire. Le pouvoir qui voudrait se faire aimer à tout prix finit dans le mépris, se fait honnir et conspuer.

L’opposition du résultat et de l’intention sévit dans toutes les activités, mais surtout au plan politique. Aussi, personne ne saura prévoir quand et comment s’achève une entreprise. C’est le paradoxe des conséquences.

Ce tragique de l’action est fonction des aléas de la vie.

Il n’est, tout d’abord, obtenu à la fin que ce que l’on se donne au départ.

Le mensonge ou l’utopisme ne peuvent que produire méfiance et hostilité.

Ensuite, l’histoire est faite de négligences, d’omissions, de déceptions, de retournements et surtout d’antagonismes irréductibles.

Avec des moyens limités on ne peut accomplir des fins illimitées.

Ces fins sont elles-mêmes multiples et inconciliables.

Une fin ultime est nécessairement théorique ; elle ne peut entraîner que des conséquences elles aussi théoriques.

Aussi, faire croire que les effets attendus d’une action faite dans de bonnes intentions serait bonne ne peut être qu’imposture.

Ainsi, ceux qui voulurent supprimer le mur de Berlin pour lubrifier l’export des valeurs bourgeoises, auront importé le communisme du marché unique.

L’Union Européenne hisse-t-elle le pavillon du thalassocratisme proxéniste qu’elle devient le champ de foire de la traite humanitaire.

La religion des droits pave les autoroutes aux rois de l’homme.

Pis encore, il est des projets qui s’abîment en leur contraire (énandrodomie) : l’hyperglobalisme enclôt et confine ; l’écologisme pollue ; le spécisme déshumanise ; le décolonialisme conchie l’universalisme !

Rien ni personne n’y échappe.

Même l’utopie de plan collectif est pareillement soumise à cette loi historique.

Laïcité est cache-sexe du déchainement des paroisses contre les non-paroisses ; l’ultra sexisme genré de l’un est inimitisation de l’autre ; l’anti-racisme s’abîme en hyper-racisme. La cause de la critique-critique finit dans l’hypercriticisme autophage et autodévastateur. Etc…

L’avenir n’est donc jamais programmé, ni programmable. Prédiction et prophétie ne font pas prévision. En politique enfin, il n’y a ni espoir, ni désespoir absolus.

III/ L’APOLOGUE DU CHIFFRE 3 ET DU TIERS

Julien FREUND opinait que la sociologie s’ouvrait à partir du chiffre 3, parce que la relation sociologique a pour fondement numérique le chiffre 3 et que la dialectique met en jeu des contradictions que l’on peut dépasser intellectuellement dans un 3ème terme. Le couple qui procréée fait communauté à partir du nouveau-né.

![Sociologie_du_conflit___Julien_[...]Freund_Julien_bpt6k4806958w.jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/00/01/684065293.jpg) Si le 0 est mode de mise à zéro de ce qui précède, le non-lieu du désenchantement, du dépérissement, de la dépolitisation, soit non-Etre, le 1 est constellation de la monocratie, de la violence (par refus du combat), de l’asservissement. C’est le monde des échanges à somme positive : il n’y en a qu’un qui gagne.

Si le 0 est mode de mise à zéro de ce qui précède, le non-lieu du désenchantement, du dépérissement, de la dépolitisation, soit non-Etre, le 1 est constellation de la monocratie, de la violence (par refus du combat), de l’asservissement. C’est le monde des échanges à somme positive : il n’y en a qu’un qui gagne.

Le 2 est cosme du dualisme donc du conflit de personnes, de valeurs, de systèmes de valeurs, mais aussi de l’amitié et de l’amour, de l’ami et de l’ennemi, de la terre et de la mer.

Le 3 est l’empire du tiers, celui qui rend possible la relation de majorité à minorité, de gouvernants à gouvernés, de l’individu au groupe. La reconnaissance du tiers assure la stabilité et la concorde. L’irruption du tiers conjure la relation au polémogène et au conflictuel. Le tiers c’est l’arbitre, le médiateur, le juge, l’intercesseur, l’avocat. Il domestique les contraires, canalise leur violence, lubrifie l’agonalité.

Dans une guerre, le tiers peut surgir et modifier le rapport de force bilatéral.

Ce tiers est la plaque tournante de toutes les alliances et des configurations possibles de coalition. Itou au plan social, électoral ou concurrentiel.

Toute alliance a pour fondement le tiers. La présence ou l’absence de tiers bouleverse les conflits. Le tiers, a, en effet, le choix de la combinaison amitié, hostilité ou indifférence. Soit il rompt la dualité de l’ami et de l’ennemi ; soit il lubrifie et impose entente, compromis, transaction.

C’est lui qui fait la paix ou fabrique le compromis (la plus belle invention des hommes avec la roue).

Ainsi considéré, il pousse ou empêche l’affrontement en équilibrant, rééquilibrant ou déséquilibrant. C’est à l’aune du tiers encore que se mesure la tolérance ou l’intolérance. La tolérance se fonde sur le tiers inclus, c’est-à-dire le droit des tiers à exprimer opinion, pensée, projet. A l’inverse, l’intolérance participe du tiers exclu.

Le 3 et le tiers opèrent césure d’avec le 2 mais ouverture vers le 4 et plus.

Ils permettent le passage dans le non numérable, le qualitatif et la mise en forme-forme.

La pensée triadique perce une brèche décisive dans l’habitus intellectuel de la doxa du monopolaire et du bipolaire.

La quête du tiers est donc maxime politique qui allie ou sépare, fédère ou oppose, associe ou dissocie. Le tiers peut aussi être l’instigateur ou le profiteur du conflit, celui qui pousse à l’amitié ou à la haine.

A cet égard, au sein de l’instance culture et dans l’essence de l’économique, le tiers est-il l’argent. Il y est le référent général et abstrait, le convertisseur et le régulateur, le valorisateur et le dévalorisateur. Il assume la fonction de différenciation et d’indistinction. Comme fait de culture, la mise en abstraction numérique intellectualise et acculture, au calcul, à la machination. Il est le tiers vicieux du vice de la triple morale du psaume libéral, qui veut faire croire que 2 + 2 = 5. Mais avec ses sous-jacents fabrique le zéro ou le moins un ! ce qui induit la question du technique et surtout du technologique.

Pour Julien FREUND, le technique est la dialectique des dialectiques. Elle opère par combinaison des moyens, des agencements et des procédures.

Le technique est donc médiation mais elle est serve en tant qu’elle est au service de la science, de la puissance, de l’esthétique, du politique, de la culture, de l’économie, etc… et leurs fins. La technique est alors la décision de ceux qui l’utilisent, la détiennent ou la précipitent dans l’antagonisme des fins. Associative ou dissociative, quelle est-elle ? Serait-elle nouveau rapport de commandement à obéissance, de maître à esclave ou de satisfaction des besoins qu’elle créerait par elle-même ? Serait-elle, au final, l’essence des essences ? Elle n’est dès lors pas neutre, ni donc le tiers attendu. Tout change avec la technologie. Celle-ci s’arroge le droit de poser ses propres fins, présupposés et moyens. Son autonomisation téléologique et sa dimension normative face au politique, à l’entreprenariat, à l’éducateur ou au militaire est gros d’une conflictualité avec les propres exigences téléologiques de ces dernières activités.

Le technique est donc médiation mais elle est serve en tant qu’elle est au service de la science, de la puissance, de l’esthétique, du politique, de la culture, de l’économie, etc… et leurs fins. La technique est alors la décision de ceux qui l’utilisent, la détiennent ou la précipitent dans l’antagonisme des fins. Associative ou dissociative, quelle est-elle ? Serait-elle nouveau rapport de commandement à obéissance, de maître à esclave ou de satisfaction des besoins qu’elle créerait par elle-même ? Serait-elle, au final, l’essence des essences ? Elle n’est dès lors pas neutre, ni donc le tiers attendu. Tout change avec la technologie. Celle-ci s’arroge le droit de poser ses propres fins, présupposés et moyens. Son autonomisation téléologique et sa dimension normative face au politique, à l’entreprenariat, à l’éducateur ou au militaire est gros d’une conflictualité avec les propres exigences téléologiques de ces dernières activités.

Gageons que l’hégémonie du technologique fera exploser le plan collectif de l’utopie, mettra à néant l’idéologie moderne et installera l’inégalitaire et fabriquera de nouveaux dieux et titans ! Ce qui ouvrira la voie à une nouvelle connivence entre la technologie et la mentalité européenne native.

S’en suivra nouvelle redistribution des cartes, nouvelles intuitions du monde, nouvelles religions, nouvel l’art, nouvelles politiques, nouvelles économies…Le défi de la pensée est dans l’inversion des inversions.

IV/ LE PENSEUR DE L’ANTI DECADENCE

Pour Julien FREUND le concept de décadence est « un concept historique ». Ce qui veut dire d’abord qu’il n’existe pas de décadence absolue. La décadence appartient au monde de l’existence représentée et non à celui d’un monde non existant préfiguré comme devant exister un jour. Aussi le contraire de décadence n’est pas le progrès mais la germinalité.

Ensuite, l’idée de décadence implique une situation qui est en dépression, en voie de détérioration par rapport à un état antérieur qui était en état d’extension, de puissance et d’harmonie d’entre les essences.

Enfin, la décadence n’est pas un terme, une fin de l’histoire, mais la clôture historique d’une civilisation. La décadence ouvre un interrègne en attendant qu’un autre type de civilisation lui succède.

Julien FREUND s’est longuement penché sur la décadence de l’Europe.

Il note à son égard l’épuisement énergétique, la migration de ses instincts vitaux, le désenchantement. Singulièrement il prend acte que l’Europe a quitté l’Europe, qu’il n’y a plus de préjugés européens, que les Européens ont perdu jusqu’à la symbolique agressive.

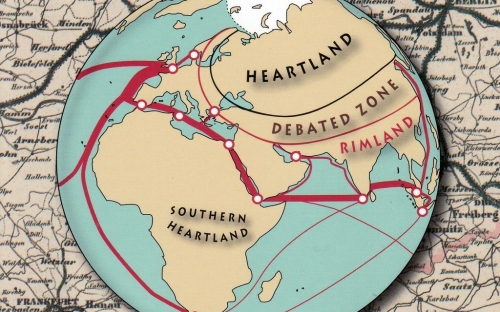

Ils passent leur temps à s’unir pour s’unir comme les faibles alors que l’union naît de la volonté de réaliser une œuvre commune. Ils n’ont plus le sens ou la posture géopolitique et geomythique.

Les Européens refusent de désigner l’ennemi. Ils oublient que l’ennemi les désigne. Or si leur civilisation succombe c’est qu’elle est victime de ses ennemi.

Ces derniers ne cachent nullement leur dessein d’anéantissement. Et lui fait perdre le Nord. Lui prendre le Septentrion. Moissonner sa sagesse.

Les Européens, par ricochet, intègrent dans leur comportement des incitations à la lâcheté ensuite précisément du dressage idéologique par tromperie sur l’ennemi fraude de l’ennemi et colonisation.

Pis encore, l’Europe se pique de se culpabiliser collectivement. Elle revendique la dépravation comme morale.

A ne plus vouloir d’ennemi, elle demeure l’ennemi pour ses ennemis. Elle a beau manifester bienveillance, pacifisme et humanitarisme.

Julien FREUND prend le soin de départir la décadence endogène d’avec la mise en décadence-décadance exogène.

La décadence revient à dissocier les fonctions très précisément opérer ou subir rupture au niveau de la 1ère d’elles, divorce du politico-religio-esthétique, l’obésité de l’économie ou l’éthisme de contrebande.

Ainsi, par application de la théorie des instances et des essences, la décadence s’analyse en domination des instances sur les essences. La politique prostitue le politique ; la technique met au pas ; le droit-loi oblige, discipline, déontologise dans la légalité de l’illégitimité ; la culture ritualise la programmatique des contraires ; le social thésaurise.

Il stigmatise ensuite la décadence par les Européens eux-mêmes en tant que processus accepté de défiguration, répudiation, dévitalisation des formes de vie, principes et fondements de leur civilisation par humanitarisme. Qui est tricherie.

Mais surtout, Julien FREUND croise le fer avec l’entreprise de mise en dédacence-décadance. (Théorie du choc, grande inversion, levées des armées de réserve du capital depuis les extrémités de la terre) et l’entreprise de prise qui guigne le territoire, la munificence, la magnificence des Européens, en même temps qu’elle orchestre leur dépossession, dévastation, élimination. (Précisons qu’Europe a pour radical le verbe ropein qui signifie débroussailler, sarcler, plumer, piller… !).

Mais surtout, Julien FREUND croise le fer avec l’entreprise de mise en dédacence-décadance. (Théorie du choc, grande inversion, levées des armées de réserve du capital depuis les extrémités de la terre) et l’entreprise de prise qui guigne le territoire, la munificence, la magnificence des Européens, en même temps qu’elle orchestre leur dépossession, dévastation, élimination. (Précisons qu’Europe a pour radical le verbe ropein qui signifie débroussailler, sarcler, plumer, piller… !).

Voyez la religion de l’Etat qui est la guerre civile de religion.

L’Etat sait, en effet, qu’il ne peut garantir les promesses et présupposés qu’il pérore. Il échoue même dans le faire-croire. De là sa violence augmentée. S’y ajoute que le gouvernement des peuples est affaire théocratique et non plus politique.

L’obsession humanitariste désigne l’ennemi intérieur. Elle fait de l’Etat un commis de la violence privée. Et cette violence de répéter la concurrence de violence sous le patronage culturel de cette violence.

Elle œuvre à la dissociation et verse dans l’impolitique, l’anti-politique, la politicoclastie. Le statut de citoyen est bouleversé. Le ressortissant politique de la cité est banlieusé, déculturé de force, acculturé à une théologie violente, matinée de traites financière (la dette), égalitaire et anthropologique, discriminé socialement, racisé et déracisé, par les suprémacismes publicitaires, traqué par les diasporas sur son propre sol.

L’Etat fait sa course théoidéologique contre le peuple, contre ses citoyens pour compte d’autrui. C’est l’apparente nouveauté de la situation. Il n’en est rien. Loin de trahir il accomplit sa mission. L’Etat a vocation d’accoutumance à l’humanitaroïté. Clovis a prêté serment à la doctrine magique de la décadance et tous ses successeurs avecque ! L’état de l’Etat est de servir l’hétérotopisation, de privilégier l’altérité étrangère et de maltraiter l’indigénie autochtone.

Là sont métaconstitution et prérequis de la ré-priva-blique.

Ici on hystérise la proxénie. La migrance est le star-système de la jet secte. La finalité intrinsèque va à la suppression du peuple politique. L’ennemi total c’est le peuple : les francs(s)ais, les Blancs, les boréens, les rétifs à l’hétérogénisation.

Le paradoxe veut toutefois que la civilisation moderne entre elle-même de plain pied dans la décadence et la conflagration d’avec le concept de progrès. Ainsi, le vice sature, la perversion viralise. S’il n’y a plus que des individus il n’y a pas même de société, et la souveraineté va aux gangs des rois de l’homme.

Pour Julien FREUND l’idée de décadence indique que tout système, tout antisystème, tout concept, toute conception du monde vont s’effondrer, être balayée, évacuée.

Une idée archaïque peut toujours reparaître sous d’autres formes ; ce que l’homme a pensé, il peut à nouveau le penser ; ce qu’un peuple a fait il peut à nouveau le faire. La décadence appelle à la renaissance. Le destin est dans l’origine.

Une idée archaïque peut toujours reparaître sous d’autres formes ; ce que l’homme a pensé, il peut à nouveau le penser ; ce qu’un peuple a fait il peut à nouveau le faire. La décadence appelle à la renaissance. Le destin est dans l’origine.

A une religion qui se meurt succède une autre religion. Le sursaut charismatique gros d’un nouvel âge est toujours là. L’aventure d’avec l’histoire peut prendre ou reprendre à tout moment.

Il suffit d’une étincelle pour raviver le feu. Tous ont rendez-vous avec le tragique, l’entropie, l’enandrodomie, l’hétérotélie. Une théocratie qui aura perdu son dieu en route est nécessairement bouleversée.

Sa déseschatologisation est inévitable. La fin du monde biblocentré arrive à grands pas. Le messianisme dévisse de mythe en philosophie, de technique en routine. Voyez la mise en ballet des écuries régulières et séculières des monothéismes et la promotion népotiste du mahométisme. Les schémas mentaux explosent.

Les peuples sis en Europe furent abîmés, épuisés, disqualifiés en ayant été amenés à épouser des causes, soutenir des conflits, se prostituer à des intérêts, valeurs et mythes qui ne sont pas les siens.

V/ LA GRANDE LEÇON ET LE CAS PRATIQUE DU MOMENT

En posant sa théorie des essences et des instances, Julien FREUND aura pensé un système contre les anti-systèmes. Son œuvre se lit comme un traité du permapolitique et de macropolitisme. Sa philosophie confine en savoir absolu pensé dialectiquement. Mais gardons-nous de ranger Julien FREUND dans la seule armoire de la politique car le souci du Maître de VILLE aura été de penser et de répondre à la nécessité métapolitique et métaphysique.

Julien FREUND est décolonisateur. Il inverse l’inversion et remet les choses à l’endroit. Il arrache les masques. Son code secret est l’éthique du succès. Mais c’est une grammaire de retour à la mesure : la mésocratie. Julien FREUND est un mésocrate. Mais non point un misocrate. Sa structure narrative vise au renversement des idioties disciplinaires. Le cahier des charges de son offre théorique s’articule comme suit : il faut affirmer les principes fondamentaux pour défendre et sauver l’Europe et ses peuples contre leurs ennemis et défier la mise en décadence-décadance.

Fondamentalement, l’enveloppe des essences est le liquide amniotique desdits peuples qui protège leur substance primordiale.

Au commencement il y a les 6 essences (l’artistique, l’économique, l’éthique, le politique, le religieux et le scientifique). Une essence est une activité catégorisée, critérisée et détectable par une donnée, des présupposés et une finalité spécifique. Ces activités sont premières et primaires, vitales et constantes.

La mise en relation de ces essences donne lieu à des activités secondaires ou dialectiques. Il s’agit des instances au nombre de 5 : le culturel, le juridique, le pédagogique, le social et le technique. Nous y ajoutons la politique par souci de clarification.

Ces essences sont des outils conceptuels visant à dominer l’expérience et à sanctionner les débordements, insuffisances ou carences. Mésocratie harmonique toujours erigée en système.

Julien FREUND n’aura eu de cesse que de scruter les oscillations des présupposés par lui identifiés, les mouvements des essences et des instances, à la fois entre elles et contre elles.

Sa grille expertise les dynamiques des peuples ou leurs morbidités. Et de leur appliquer son curseur, sa grammaire, son contrôle.

Le signe manifeste de la décadence est l’hégémonie d’une essence sur toutes les autres ou la domination des instances sur les essences. Tel est le cas si la politique prostitue le politique, si le droit déontologise la légalité de l’illégitimité ou si la technique met au pas. Car alors les essences sont expulsées de l’être et les instances gèrent la marche forcée vers le non-être. De même Julien FREUND développera également une conception du droit inouïe de justesse. Parce qu’irriguée de la musicalité du juste. Chaque citoyen a vocation à prendre sa part ; est injustice celui qui prend plus ou moins que sa part ; la part prise par le créancier diasporique est acmé de l’illégitime.

L’économisme fit muer l’économie en religion et commuer l’économique de la satisfaction des besoins à religion du besoin de satisfactions.

Le politique fait irruption quand survient une variation dans les associations et les dissociations. A partir d’un certain seuil, l’effet de cliquet opère bascule. La quantité devient qualité. Telle opinion, telle image, tel slogan fédèrent des amitiés nouvelles, les relient autour d’une désobéissance, défie le commandement et désigne l’ennemi.

Le constat de l’entrée en politique-politique est aisé. La vision de la rue suffit si à la lutte qui y préside s’ajoutent masses, répétitions, slogans et violence... A l’inverse, une procession de robins n’est pas politique.

Tout autre est la montée au front d’une sainte alliance eschatologique qui agite « Grande remise à zéro », coronarise une pandémie et fait déclaration de guerre aux Etats-Nations. Ce « projet collectif » d’initiative privée, purement privative, vise à agresser les peuples dans leur intégrité physique, dans leurs organismes de protection sanitaire, dans leurs budgets sociaux, dans leur fonction économique et dans leur souveraineté financière. Pareille décision est nécessairement politique.

Julien FREUND a en stock 10 catégories d’objections-obstacles à ces menées :

Julien FREUND a en stock 10 catégories d’objections-obstacles à ces menées :

En premier lieu, cette manifestation d’hostilité caractérisée est hautement politique quand bien même procéderait-elle d’un déplacement à l’extrémité du pôle privé au fondement d’une « opinion » théologique catapultée, « commandement » motorisé ;

En second lieu, les peuples cibles sont « livrés au regard de l’ennemi » ; c’est donc lui « qui nous désigne » comme l’ennemi d’icelui ; il devient dès lors le nôtre ;

En troisième lieu, ceux qui de droit et par fonction ont mandat et « pouvoir de nous protéger » mais s’abstiennent, défaillent ou s’y refusent, se disqualifient ; ils dévissent dans « l’impolitique ».

En quatrième lieu, la décision de l’ennemi de « faire la guerre » opère passage à la guerre privée donc à la « guerre civile de religion » - la pire de toute ;

En cinquième lieu la répression policière de la résistance, sous quelque moyen ou prétexte que ce soit, devient « violence privée oppressive en tant qu’elle voudrait éliminer ou empêcher tout conflit » en cette occurrence ;

En sixième lieu, « le rapport de force du fort au faible » est renversé ; mais le pouvoir ennemi d’indirect (potestas indirecta) devient direct (directa) donc dévoilé, ostenstible, visible – immédiatement politique.

En septième lieu, se constate une montée aux extrêmes de la « peur de la peur », de la « contrainte psychique » et de dressage techno-vétérinaire aux effets insoupçonnés pour les méchants organisateurs : toute dénaturation de l’animal-homme est grosse de sur-naturation qui se déchaînera immanquablement contre les élites nolochistes ;

En huitième lieu, la cadence s’actualise en décadance comme praxis de la destruction, de la déconstruction, de la dévastation ; soit « les formes politiques extrêmes de la décadence » ;

En neuvième lieu, « l’éthique de la conviction » mondialisée s’élève à la criminalité cosmopolitiste ; la guerre à l’humanité est crime éponyme ; le massacre de classe demeure « massacre » ;

En dixième lieu : la tyrannie des valeurs signe machination de mise en non-valeur.

N’oublions jamais que valeur vient du latin valor et signifie force de vie, énergie de vie, puissance. Vaut ce que pose un peuple ou lui impose l’ennemi.

D’aucuns voudraient-ils commuter la condition humaine en condition juridique vers le zoologique ou la chosification, Julien FREUND moqueur tragique de leur objecter que toute entreprise demeure soumise au paradoxe des conséquences et que tout plan collectif peut entrer en décadence jusqu’à s’effondrer. Ainsi entendue décadence n’est autre chose que la sociologisation de la chute de la modernité, l’agonie de l’aire actiaque, donc la clôture du temps de l’historiette du désert.

D’aucuns voudraient-ils commuter la condition humaine en condition juridique vers le zoologique ou la chosification, Julien FREUND moqueur tragique de leur objecter que toute entreprise demeure soumise au paradoxe des conséquences et que tout plan collectif peut entrer en décadence jusqu’à s’effondrer. Ainsi entendue décadence n’est autre chose que la sociologisation de la chute de la modernité, l’agonie de l’aire actiaque, donc la clôture du temps de l’historiette du désert.

Cette loi de l’histoire conduque et sanctionne toute intention et action y compris les menées décadentistes. Ainsi, les dystopistes, déconstructivistes ou ravageurs soromanes échoueront. Leur one-way versera dans le cul de sac. Leur prophétie de s’étioler comme rots dans le cosmos. Par voie de conséquence, la décadence peut devenir elle-même une condition de renouvellement de la pensée et de l’action donc de l’histoire. La fin d’un type de civilisation percluse d’inversion ne peut que s’inverser dans l’inversion. La théorie de la décadence est boule des oscillations, ondulations, rétro ou rotofagies du tragique. A nouveau, décadence signe fin d’une cabbale non celle du monde. L’inversion d’inverser l’inversion. L’économisme ne saurait jamais fusionner l’autorité spirituelle et l’autorité temporelle. Une fonction ancillaire ne saurait jamais prétendre à faire fondement. Elle reste une technique de prise. Une valeur unique n’est pas valeur.

La métaphysique de l’illimité qui s’arcboute sur une seule essence ou une seule instance, tel un pied de biche, dévoile l’effraction de son réductionnisme, sa monocult-ure, son monothéisme du marché !

VI/ LA FIGURE DU CLASSIQUE

Julien FREUND doit être calibré comme un classique du politique (du latin classis troupe de première classe).

Il fut un résistant inflexible sa vie durant contre tous les envahissements, toutes les impostures et toutes les pollutions de l’esprit.

Servi par une rhétorique implacable et de son rire ravageur, Julien FREUND s’imposait par sa pétulance, sa pertinence et sa profondeur.

Un facies de celte rayonnant, un prénom d’empereur romain, un nom dialectiquement contraire d’ennemi.

L’amitié politique restera chez lui la finalité des finalités : primat germinal.

Le vrai vaccin contre l’impolitique, l’anti-politique ou la politicoclastie, c’est lui ; la défense immunitaire faite pensée politique c’est encore lui. Le classique c’est toujours lui.

Il a passé sa vie à enseigner – instituteur à 17 ans -, à professer – dans le secondaire puis à l’Université de STRASBOURG -, à plaider pour la cause des peuples d’Europe. Ce géant aura eu une vie agitée, trépidante, dangereuse. Il fit la guerre en partisan. Il connaîtra le choc des incultures. Il fut surtout le pôle de la résistance au pouvoir culturel.

Il est totalement méconnu que Julien FREUND jouera un rôle de sage. Les puissants vinrent le consulter, sollicitèrent son arbitrage ou recueillirent son expertise. Les amoureux de sa sagesse, accoururent à Villé pour s’y abreuver. Lui encore se repaîtra des échanges, du ressenti, des sentiments de ses concitoyens. Julien FREUND incarne ce savoir gravitationnel qui fait, à la fois, la physique, la métaphysique et l’impérissabilité de sa conception du monde. Ses intuitions et théories font sens, donnent sens et fournissent les concepts opérationnels pour la lutte.

Au vu de ce qui précède, il est aisé de constater que la pensée de Julien FREUND est toujours valable. Elle porte date mais n’est pas datée. Elle est de toujours. Elle relève de la sagesse classique. Elle fait récit. Elle est puits de science. Le Freundisme est la technique qui fonctionnalise la théorie des essences et des instances. Le rôle du classique est d’être à l’affût du princeps de son époque et de proposer le principe ordonnatif. Le classique est celui qui devient grand dans le fond de son essence, voit les grandes choses de ses essences et entre dans leur suite. Fondamentalement ainsi, le politique ne saurait dépérir. Il est insurmontable, incompréssible, incontournable. Il est essence. Elle pèse. Parce que nécessité vitale. Pour lui encore l’univers est indéterminable. Il n’y a pas de sens de l’histoire. L’histoire ne suit pas un cours obligatoire. Là est la banalité supérieure du Freundisme, c’est-à-dire génie.

Le classique est le fils de son temps et de l’espace qu’il habite. Il est armé de la lucidité de l’expérience historique. Il fournit un fil d’Ariane pour guigner le salut collectif.

Le classique envisage toujours le pire pour qu’il n’arrive jamais. Il fabrique donc les scénarii et pense les moyens pour faire face en cultivant les ressources intraspécifiques. Car le maître de Villé aura fait de la politique, affronté l’anti-politique et tutoyé l’impolitique. Il aura retenu que la pesanteur du politique est dans la lutte contre l’ennemi.

L’actualité, la pertinence et le succès de la pensée de Julien FREUND sont inversement proportionnels à l’inactualité, au silence et à la censure pratiquées par les appareils de la manipulation idéologique.

Au vrai Julien FREUND aura mobilisé, tout au long de sa vie, son énergie contre la malfaisance et la malpensence. Ses concepts sont des armes. Il a toujours soutenu que poser s’est s’opposer. Aussi, sa pensée est-elle, à la fois, affirmation de son gai savoir et révocation de l’illégitimité du monde contemporain.

Comme champion de la limite et de la mesure, il ouvre un au-delà au marigot de l’illimité et la démesure, c’est-à-dire l’ultra-capitalisme, l’humanitarisme ou l’hyper-racisme de l’anti-racisme.

Il nous force à penser l’ennemi en son entreprise de cabbale, ses valeurs boursières, sa tyrannie dévastatrice, son aliénation aliéniste. Il nous présente une autre méta-constitution, alternative et franche de toute théologie mortifère. Sa philosophie n’est pas idéaliste mais vaut grammaire de conquête et de re-conquête c’est-à-dire orthographie de la puissance politique. Son œuvre est donc un traité de contestations de la mise en marchandise.

Julien FREUND pense la totalité du nomos politikon. L’extrême amitié pour les siens l’aura poussé à inventer le peuple politique comme figure de l’alternative. Parce qu’il est le penseur non aligné par excellence de l’ordre néo-libéral, il nous invite à imaginer et forcer la scission d’avec la mise en ordre économiste comme possible d’une autre forme historique que la cage d’acier du capitalisme. Sa théorie des essences et des instances est alors piédestal pour penser, construire et produire cette alternation politico-historique. Son grand mérite aura été d’oser penser le sens de la possibilité d’une possibilitas.

Son programme total est le réenchantement par la repolitisation. Son offre est toute de panache et d’aspiration à la cité du politique-politique.

Julien FREUND se sera fait un devoir cavalier et heuristique envers la cité en tant que toit physique et métaphysique. Freund docet Boreanos.

Vive la FREUNDopolis !

Jean-Louis FEUERBACH.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

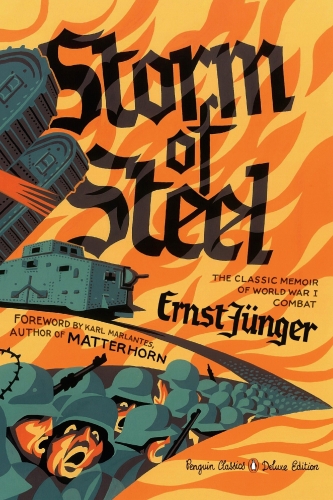

Embarrassés par un tel désastre, ces hommes "civilisés" ont dû faire face au fait que leur seule arme et leur seul espoir était la volonté, et leur seul monde les camarades du front. Derrière eux se cachaient les fiers idéaux des Lumières. Le jeu de la vie dans les bonnes formes et la rhétorique pamphlétaire parisienne étaient enfouis dans la boue de Verdun et de la Galice, dans les rochers du Carso et dans les eaux froides de la mer du Nord.

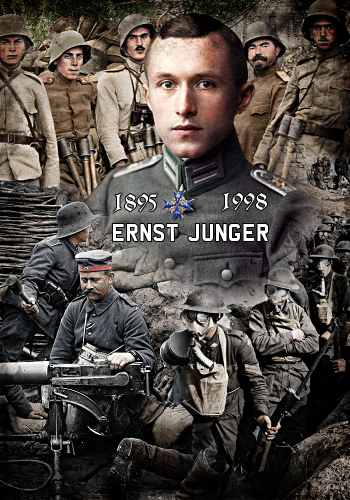

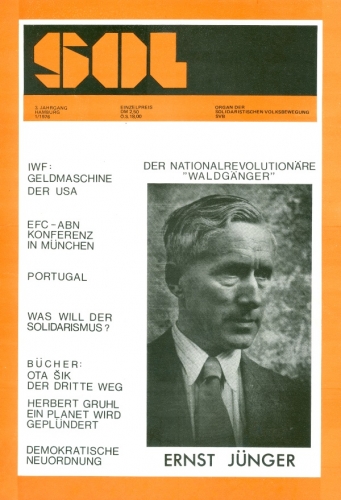

Embarrassés par un tel désastre, ces hommes "civilisés" ont dû faire face au fait que leur seule arme et leur seul espoir était la volonté, et leur seul monde les camarades du front. Derrière eux se cachaient les fiers idéaux des Lumières. Le jeu de la vie dans les bonnes formes et la rhétorique pamphlétaire parisienne étaient enfouis dans la boue de Verdun et de la Galice, dans les rochers du Carso et dans les eaux froides de la mer du Nord. Jünger alla beaucoup plus loin ; il comprit que ce conflit avait détruit les barrières bourgeoises qui enseignaient l'existence comme une recherche de la réussite matérielle et l'observation de la morale sociale. C'est alors que les forces les plus profondes de la vie et de la réalité ont émergé lors du conflit, ce qu'il a appelé les "élémentaires", des forces qui, par une mobilisation totale, sont devenues une partie active de la nouvelle société, composée d'hommes jeunes et durs, une génération abyssalement différente de la précédente.

Jünger alla beaucoup plus loin ; il comprit que ce conflit avait détruit les barrières bourgeoises qui enseignaient l'existence comme une recherche de la réussite matérielle et l'observation de la morale sociale. C'est alors que les forces les plus profondes de la vie et de la réalité ont émergé lors du conflit, ce qu'il a appelé les "élémentaires", des forces qui, par une mobilisation totale, sont devenues une partie active de la nouvelle société, composée d'hommes jeunes et durs, une génération abyssalement différente de la précédente.

Au début des années 1930, une série d'écrivains sont apparus en Europe, surtout en Allemagne, dont les œuvres se référaient à la relation entre l'homme et la technique, où la volonté comme axe de la vie résulte en une constante. C'est le cas de L'homme et la technique d'Oswald Spengler - qui reprend les prémisses nietzschéennes de La volonté de puissance -, de la philosophie de la technique de Hans Freyer, de l’idée d’une perfection et de l'échec de la technique de Friedrich Georg Jünger - frère d'Ernst - et des séminaires du philosophe Martin Heidegger, tous contemporains du Travailleur, ouvrage précité. (Le livre de son frère Friedrich a été publié immédiatement après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, mais il avait été écrit de nombreuses années auparavant et les vicissitudes du conflit l'ont empêché de voir le jour). Mais ces questions n'étaient pas uniquement du monde germanique, car il ne faut pas oublier les futuristes italiens dirigés par Filippo Marinetti, ni Luigi Pirandello de Manivelas, les écrits du Français Pierre Drieu La Rochelle - comme La Comédie de Charleroi - et le film Modern Times, de Charles Chaplin.

Au début des années 1930, une série d'écrivains sont apparus en Europe, surtout en Allemagne, dont les œuvres se référaient à la relation entre l'homme et la technique, où la volonté comme axe de la vie résulte en une constante. C'est le cas de L'homme et la technique d'Oswald Spengler - qui reprend les prémisses nietzschéennes de La volonté de puissance -, de la philosophie de la technique de Hans Freyer, de l’idée d’une perfection et de l'échec de la technique de Friedrich Georg Jünger - frère d'Ernst - et des séminaires du philosophe Martin Heidegger, tous contemporains du Travailleur, ouvrage précité. (Le livre de son frère Friedrich a été publié immédiatement après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, mais il avait été écrit de nombreuses années auparavant et les vicissitudes du conflit l'ont empêché de voir le jour). Mais ces questions n'étaient pas uniquement du monde germanique, car il ne faut pas oublier les futuristes italiens dirigés par Filippo Marinetti, ni Luigi Pirandello de Manivelas, les écrits du Français Pierre Drieu La Rochelle - comme La Comédie de Charleroi - et le film Modern Times, de Charles Chaplin.

Son actualité tient à la géopolitique mondiale et à l’importance croissante du pays de Chung Kuò sur le plan économique et stratégique, mais aussi à l’exotisme de formulations littéraires du texte, inspirant une tradition de savoir dont l’ambiguïté, comme celle des écrits de Lao Tse, est susceptible d’interprétations multiples. Par ailleurs, l’actualité de L’Art de la Guerre découle de la somme des dilemmes et des interrogations que les hommes de pensée et d’action doivent résoudre dans les drames individuels de leur vie, ou dans les engagements collectifs de leurs peuples ou encore dans les questionnements imposés par des situations graves, de danger existentiel et de menace imminente.

Son actualité tient à la géopolitique mondiale et à l’importance croissante du pays de Chung Kuò sur le plan économique et stratégique, mais aussi à l’exotisme de formulations littéraires du texte, inspirant une tradition de savoir dont l’ambiguïté, comme celle des écrits de Lao Tse, est susceptible d’interprétations multiples. Par ailleurs, l’actualité de L’Art de la Guerre découle de la somme des dilemmes et des interrogations que les hommes de pensée et d’action doivent résoudre dans les drames individuels de leur vie, ou dans les engagements collectifs de leurs peuples ou encore dans les questionnements imposés par des situations graves, de danger existentiel et de menace imminente.

La subtilité du coup d’œil et la rapidité d’exécution décident de la réussite immédiate et à long terme. Elles fondent dans l’instant, l’esprit et l’âme de l’action du stratège. Voir, agir et vaincre le futur se dévoilent totalement dans l’instant, dans l’occasion fugace, dans la saisie d’un acte, dans un détail divinatoire. Voir, interpréter et agir exigent de passer par des manifestations infimes, par un coup de regard et une étincelle des yeux ! Il faut saisir toutes les implications d’un acte par une décision foudroyante ! Agir sur le futur, c’est acter dans les amonts du temps, c’est penser la durée dans l’instant, c’est troubler l’ordre absolu par l’irruption du chaos, c’est former par l’informe, dans toute la profondeur des temps. La victoire, dans l’ordre absolu, est le fruit de l’ordre intérieur, brisant la législation du prévisible. C’est frapper par l’imparable, portant atteinte aux vertus du paisible. C’est là que la lame scinde la lumière de ses origines et coupe le regard de l’homme pour le faire rentrer dans les ténèbres de la nuit et dans celles du vide. Dans la domestication de la guerre et des conflits permanents, quatre écoles mènent le jeu et orientent les solutions dans la Chine ancienne :

La subtilité du coup d’œil et la rapidité d’exécution décident de la réussite immédiate et à long terme. Elles fondent dans l’instant, l’esprit et l’âme de l’action du stratège. Voir, agir et vaincre le futur se dévoilent totalement dans l’instant, dans l’occasion fugace, dans la saisie d’un acte, dans un détail divinatoire. Voir, interpréter et agir exigent de passer par des manifestations infimes, par un coup de regard et une étincelle des yeux ! Il faut saisir toutes les implications d’un acte par une décision foudroyante ! Agir sur le futur, c’est acter dans les amonts du temps, c’est penser la durée dans l’instant, c’est troubler l’ordre absolu par l’irruption du chaos, c’est former par l’informe, dans toute la profondeur des temps. La victoire, dans l’ordre absolu, est le fruit de l’ordre intérieur, brisant la législation du prévisible. C’est frapper par l’imparable, portant atteinte aux vertus du paisible. C’est là que la lame scinde la lumière de ses origines et coupe le regard de l’homme pour le faire rentrer dans les ténèbres de la nuit et dans celles du vide. Dans la domestication de la guerre et des conflits permanents, quatre écoles mènent le jeu et orientent les solutions dans la Chine ancienne : Or, si la stratégie à l’occidentale suppose l’organisation des combats en fonction du but de guerre (Zweck) et l’investissement des forces dans l’espace en fonction des combats, la stratégie chinoise conçoit le fondement de la stratégie dans l’action indirecte, comme pratique intelligente de la ruse. L’intelligence rusée du chef de guerre construit sa victoire sur le mouvement de l’adversaire, dans l’esprit même de l’ennemi. Or, si tel est un objectif important de la conduite des opérations militaires, de quelle manière peut-on assimiler une opération militaire, en particulier celle du stratège à un art, à une activité de l’âme. Comment par ailleurs, peut-on construire une philosophie ou une théorie de cet art ? Or, puisque toutes les guerres réunissent trois caractères essentiels, la violence originelle, la libre activité de l’âme et l’entendement politique, comment concilier violence et politique et dans quelles conditions justifier, au nom de l’entendement politique, l’abandon du principe d’anéantissement ou de victoire, sur l’ennemi ? Et encore, là où la décision est inséparablement politique et militaire, comment justifier un abandon du combat, qui est le seul conforme à l’essence de la guerre et à son concept pur ? Si la guerre n’est pas une réalité autonome du politique (d’après Carl Clausewitz, « la guerre a bien sa grammaire, mais non sa logique propre »), quel est le sens d’une action guerrière qui s’oriente délibérément vers la manœuvre et vers l’action indirecte, tournant le dos à la bataille et au combat ? Et pour terminer, la série des questionnements inhérents au débat stratégique, comment réconcilier le caractère historique, conditionné et déterminé d’une guerre, liée à des circonstances conjoncturelles et aux intentions politiques des belligérants, aux modèles abstraits, philosophiques et anhistoriques des guerres absolues, seuls conformes au concept pur de guerre ? En son temps, Sun Tzu suggère de « construire sa victoire sur les mouvements de l’ennemi » et cette recommandation opère par le renouvellement constant de deux modalités du combat : de « front » ou de « biais ». Or, la « puissance de l’action de biais » repose sur des ruses, des surprises et des procédées indirectes qui relèvent de l’action tactique, qui ne font appel ni à l’organisation des armés sur le terrain ni à leur réunion en vue de l’engagement. Elles appartiennent aux procédés des manœuvres hétérodoxes et à la tactique plus qu’à la stratégie.

Or, si la stratégie à l’occidentale suppose l’organisation des combats en fonction du but de guerre (Zweck) et l’investissement des forces dans l’espace en fonction des combats, la stratégie chinoise conçoit le fondement de la stratégie dans l’action indirecte, comme pratique intelligente de la ruse. L’intelligence rusée du chef de guerre construit sa victoire sur le mouvement de l’adversaire, dans l’esprit même de l’ennemi. Or, si tel est un objectif important de la conduite des opérations militaires, de quelle manière peut-on assimiler une opération militaire, en particulier celle du stratège à un art, à une activité de l’âme. Comment par ailleurs, peut-on construire une philosophie ou une théorie de cet art ? Or, puisque toutes les guerres réunissent trois caractères essentiels, la violence originelle, la libre activité de l’âme et l’entendement politique, comment concilier violence et politique et dans quelles conditions justifier, au nom de l’entendement politique, l’abandon du principe d’anéantissement ou de victoire, sur l’ennemi ? Et encore, là où la décision est inséparablement politique et militaire, comment justifier un abandon du combat, qui est le seul conforme à l’essence de la guerre et à son concept pur ? Si la guerre n’est pas une réalité autonome du politique (d’après Carl Clausewitz, « la guerre a bien sa grammaire, mais non sa logique propre »), quel est le sens d’une action guerrière qui s’oriente délibérément vers la manœuvre et vers l’action indirecte, tournant le dos à la bataille et au combat ? Et pour terminer, la série des questionnements inhérents au débat stratégique, comment réconcilier le caractère historique, conditionné et déterminé d’une guerre, liée à des circonstances conjoncturelles et aux intentions politiques des belligérants, aux modèles abstraits, philosophiques et anhistoriques des guerres absolues, seuls conformes au concept pur de guerre ? En son temps, Sun Tzu suggère de « construire sa victoire sur les mouvements de l’ennemi » et cette recommandation opère par le renouvellement constant de deux modalités du combat : de « front » ou de « biais ». Or, la « puissance de l’action de biais » repose sur des ruses, des surprises et des procédées indirectes qui relèvent de l’action tactique, qui ne font appel ni à l’organisation des armés sur le terrain ni à leur réunion en vue de l’engagement. Elles appartiennent aux procédés des manœuvres hétérodoxes et à la tactique plus qu’à la stratégie.

Dans la conception occidentale de la guerre est exclu tout principe de « limite » qui, dans la stratégie chinoise, trouve sa forme elliptique dans le désengagement et la « fuite ». L’expression plus fidèle de la philosophie chinoise est celle du « Livre des mutations » dont les figures divinatoires offrent une représentation symbolique de l’univers et une référence aux forces qui y sont à l’œuvre. Ces représentations de la « science des mutations », sont liées, depuis les origines, aux arts martiaux, à la dialectique du Yin et du Yang, au sein de laquelle il n’y a pas de négation, mais de simple dépassement. Grâce à l’art divinatoire, il est possible de déchiffrer et de prévoir ce qui est encore en germe, par l’identification des traces ou des signes avant-coureurs, des mutations ou des évènements qui se dessinent. L’énoncé philosophique selon lequel « l’occulte est au cœur du manifeste et non dans son contraire » est au cœur du système d’interprétation de la réalité contenu dans le « Livre des mutations ». Le réel se définit par son instabilité et ses configurations transitoires. Il faudra en déchiffrer les formes et en appréhender le sens afin d’en tirer parti.

Dans la conception occidentale de la guerre est exclu tout principe de « limite » qui, dans la stratégie chinoise, trouve sa forme elliptique dans le désengagement et la « fuite ». L’expression plus fidèle de la philosophie chinoise est celle du « Livre des mutations » dont les figures divinatoires offrent une représentation symbolique de l’univers et une référence aux forces qui y sont à l’œuvre. Ces représentations de la « science des mutations », sont liées, depuis les origines, aux arts martiaux, à la dialectique du Yin et du Yang, au sein de laquelle il n’y a pas de négation, mais de simple dépassement. Grâce à l’art divinatoire, il est possible de déchiffrer et de prévoir ce qui est encore en germe, par l’identification des traces ou des signes avant-coureurs, des mutations ou des évènements qui se dessinent. L’énoncé philosophique selon lequel « l’occulte est au cœur du manifeste et non dans son contraire » est au cœur du système d’interprétation de la réalité contenu dans le « Livre des mutations ». Le réel se définit par son instabilité et ses configurations transitoires. Il faudra en déchiffrer les formes et en appréhender le sens afin d’en tirer parti.

Julien FREUND disqualifie nazisme et communisme en phases préparatoires du totalitarisme de l’utopie. Il insupporte l’intolérable. Aussi, invente-t-il une théorie englobante du vécu des peuples comme acte constitutif de la contestation du projet collectif des idéologies mondiales. Il les dénonce comme sécularisation des monothéismes.

Julien FREUND disqualifie nazisme et communisme en phases préparatoires du totalitarisme de l’utopie. Il insupporte l’intolérable. Aussi, invente-t-il une théorie englobante du vécu des peuples comme acte constitutif de la contestation du projet collectif des idéologies mondiales. Il les dénonce comme sécularisation des monothéismes. Le présupposé se signale en ce qu’il polarise son opposé. Il fixe les limites entre lesquelles oscille le réel de la vie.

Le présupposé se signale en ce qu’il polarise son opposé. Il fixe les limites entre lesquelles oscille le réel de la vie.

![Sociologie_du_conflit___Julien_[...]Freund_Julien_bpt6k4806958w.jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/00/01/684065293.jpg) Si le 0 est mode de mise à zéro de ce qui précède, le non-lieu du désenchantement, du dépérissement, de la dépolitisation, soit non-Etre, le 1 est constellation de la monocratie, de la violence (par refus du combat), de l’asservissement. C’est le monde des échanges à somme positive : il n’y en a qu’un qui gagne.

Si le 0 est mode de mise à zéro de ce qui précède, le non-lieu du désenchantement, du dépérissement, de la dépolitisation, soit non-Etre, le 1 est constellation de la monocratie, de la violence (par refus du combat), de l’asservissement. C’est le monde des échanges à somme positive : il n’y en a qu’un qui gagne.  Le technique est donc médiation mais elle est serve en tant qu’elle est au service de la science, de la puissance, de l’esthétique, du politique, de la culture, de l’économie, etc… et leurs fins. La technique est alors la décision de ceux qui l’utilisent, la détiennent ou la précipitent dans l’antagonisme des fins. Associative ou dissociative, quelle est-elle ? Serait-elle nouveau rapport de commandement à obéissance, de maître à esclave ou de satisfaction des besoins qu’elle créerait par elle-même ? Serait-elle, au final, l’essence des essences ? Elle n’est dès lors pas neutre, ni donc le tiers attendu. Tout change avec la technologie. Celle-ci s’arroge le droit de poser ses propres fins, présupposés et moyens. Son autonomisation téléologique et sa dimension normative face au politique, à l’entreprenariat, à l’éducateur ou au militaire est gros d’une conflictualité avec les propres exigences téléologiques de ces dernières activités.

Le technique est donc médiation mais elle est serve en tant qu’elle est au service de la science, de la puissance, de l’esthétique, du politique, de la culture, de l’économie, etc… et leurs fins. La technique est alors la décision de ceux qui l’utilisent, la détiennent ou la précipitent dans l’antagonisme des fins. Associative ou dissociative, quelle est-elle ? Serait-elle nouveau rapport de commandement à obéissance, de maître à esclave ou de satisfaction des besoins qu’elle créerait par elle-même ? Serait-elle, au final, l’essence des essences ? Elle n’est dès lors pas neutre, ni donc le tiers attendu. Tout change avec la technologie. Celle-ci s’arroge le droit de poser ses propres fins, présupposés et moyens. Son autonomisation téléologique et sa dimension normative face au politique, à l’entreprenariat, à l’éducateur ou au militaire est gros d’une conflictualité avec les propres exigences téléologiques de ces dernières activités.

Mais surtout, Julien FREUND croise le fer avec l’entreprise de mise en dédacence-décadance. (Théorie du choc, grande inversion, levées des armées de réserve du capital depuis les extrémités de la terre) et l’entreprise de prise qui guigne le territoire, la munificence, la magnificence des Européens, en même temps qu’elle orchestre leur dépossession, dévastation, élimination. (Précisons qu’Europe a pour radical le verbe ropein qui signifie débroussailler, sarcler, plumer, piller… !).

Mais surtout, Julien FREUND croise le fer avec l’entreprise de mise en dédacence-décadance. (Théorie du choc, grande inversion, levées des armées de réserve du capital depuis les extrémités de la terre) et l’entreprise de prise qui guigne le territoire, la munificence, la magnificence des Européens, en même temps qu’elle orchestre leur dépossession, dévastation, élimination. (Précisons qu’Europe a pour radical le verbe ropein qui signifie débroussailler, sarcler, plumer, piller… !).  Une idée archaïque peut toujours reparaître sous d’autres formes ; ce que l’homme a pensé, il peut à nouveau le penser ; ce qu’un peuple a fait il peut à nouveau le faire. La décadence appelle à la renaissance. Le destin est dans l’origine.

Une idée archaïque peut toujours reparaître sous d’autres formes ; ce que l’homme a pensé, il peut à nouveau le penser ; ce qu’un peuple a fait il peut à nouveau le faire. La décadence appelle à la renaissance. Le destin est dans l’origine.

Julien FREUND a en stock 10 catégories d’objections-obstacles à ces menées :

Julien FREUND a en stock 10 catégories d’objections-obstacles à ces menées :  D’aucuns voudraient-ils commuter la condition humaine en condition juridique vers le zoologique ou la chosification, Julien FREUND moqueur tragique de leur objecter que toute entreprise demeure soumise au paradoxe des conséquences et que tout plan collectif peut entrer en décadence jusqu’à s’effondrer. Ainsi entendue décadence n’est autre chose que la sociologisation de la chute de la modernité, l’agonie de l’aire actiaque, donc la clôture du temps de l’historiette du désert.

D’aucuns voudraient-ils commuter la condition humaine en condition juridique vers le zoologique ou la chosification, Julien FREUND moqueur tragique de leur objecter que toute entreprise demeure soumise au paradoxe des conséquences et que tout plan collectif peut entrer en décadence jusqu’à s’effondrer. Ainsi entendue décadence n’est autre chose que la sociologisation de la chute de la modernité, l’agonie de l’aire actiaque, donc la clôture du temps de l’historiette du désert.

Par ailleurs, le contexte chinois est celui d'une culture dans laquelle l'école légaliste a agi en profondeur. Courant philosophique fondé au IIIe siècle avant J.-C. par Han Fei qui, en opposition aux idées confucéennes de bienveillance, de vertu et de respect des rituels, prêchait le droit du prince à exercer un pouvoir absolu et incontesté. Seule source du droit, le prince légaliste ne délègue aucune autorité à qui que ce soit. A côté de lui, il n'y a que des exécuteurs testamentaires, aux tâches strictement délimitées. En-dessous d'eux se trouvent les sujets, obligés seulement d'obéir.

Par ailleurs, le contexte chinois est celui d'une culture dans laquelle l'école légaliste a agi en profondeur. Courant philosophique fondé au IIIe siècle avant J.-C. par Han Fei qui, en opposition aux idées confucéennes de bienveillance, de vertu et de respect des rituels, prêchait le droit du prince à exercer un pouvoir absolu et incontesté. Seule source du droit, le prince légaliste ne délègue aucune autorité à qui que ce soit. A côté de lui, il n'y a que des exécuteurs testamentaires, aux tâches strictement délimitées. En-dessous d'eux se trouvent les sujets, obligés seulement d'obéir. Xi Jinping a redéfini le centre de gravité idéologique du parti communiste, redéfini la tolérance limitée de la dissidence, laquelle pouvait parfois se manifester mais a désormais disparu, de même toute forme d'autonomie, qui aurait pu être accordée au Xinjiang, à la Mongolie intérieure et à Hong Kong, a été supprimée.

Xi Jinping a redéfini le centre de gravité idéologique du parti communiste, redéfini la tolérance limitée de la dissidence, laquelle pouvait parfois se manifester mais a désormais disparu, de même toute forme d'autonomie, qui aurait pu être accordée au Xinjiang, à la Mongolie intérieure et à Hong Kong, a été supprimée.

Parmi ces intellectuels figure Georges Sorel, dont un ouvrage a été récemment réédité, l'un des moins connus de ses lecteurs. Nous nous référons à La religione d'oggi, qui est parue en librairie grâce aux éditions OAKS (pour les commandes : info@oakseditrice.it, p. 126, 16 euros).

Parmi ces intellectuels figure Georges Sorel, dont un ouvrage a été récemment réédité, l'un des moins connus de ses lecteurs. Nous nous référons à La religione d'oggi, qui est parue en librairie grâce aux éditions OAKS (pour les commandes : info@oakseditrice.it, p. 126, 16 euros). Le problème posé par Marx n'est pas, sic et simpliciter, économique, mais moral. Dans le travail en usine, l'ouvrier s'aliène sa propre condition d'être de raison. Kant, se référant dans la Raison pratique à la dignité de l'homme, n'avait fait que synthétiser les préceptes qui avaient initialement émergé de la bonne nouvelle chrétienne : "Derrière le concept d'aliénation [...] il y a la notion d'être humain développée par la philosophie moderne [...] à partir de la notion chrétienne d'égale dignité humaine" (p. XI). Quelle est la voie à suivre, selon Marx et Sorel, pour parvenir à la désaliénation ? La Révolution. Seul l'acte révolutionnaire humaniserait les circonstances historico-économiques dans lesquelles, en fait, l'homme vit concrètement. Le "soupir religieux" de la créature opprimée se transformerait ainsi en une lutte socio-politique : en elle, l'exigence éthique reste primordiale. Pour accéder aux thèses de Sorel dans le domaine religieux, il ne suffit pas de se référer au marxisme. En effet, à partir de la fin du XIXe siècle, les certitudes gnoséologiques du positivisme et du néo-positivisme ont progressivement disparu. Sorel soutient, dans le livre que nous présentons, les thèses probabilistes de Boutroux, selon lesquelles dans la sphère scientifique, il fallait toujours passer du dogmatisme positiviste au raisonnement suivant : « passer du nécessaire au probable, passer des mathématiques de la certitude aux mathématiques de l'incertitude" (p. XIV).

Le problème posé par Marx n'est pas, sic et simpliciter, économique, mais moral. Dans le travail en usine, l'ouvrier s'aliène sa propre condition d'être de raison. Kant, se référant dans la Raison pratique à la dignité de l'homme, n'avait fait que synthétiser les préceptes qui avaient initialement émergé de la bonne nouvelle chrétienne : "Derrière le concept d'aliénation [...] il y a la notion d'être humain développée par la philosophie moderne [...] à partir de la notion chrétienne d'égale dignité humaine" (p. XI). Quelle est la voie à suivre, selon Marx et Sorel, pour parvenir à la désaliénation ? La Révolution. Seul l'acte révolutionnaire humaniserait les circonstances historico-économiques dans lesquelles, en fait, l'homme vit concrètement. Le "soupir religieux" de la créature opprimée se transformerait ainsi en une lutte socio-politique : en elle, l'exigence éthique reste primordiale. Pour accéder aux thèses de Sorel dans le domaine religieux, il ne suffit pas de se référer au marxisme. En effet, à partir de la fin du XIXe siècle, les certitudes gnoséologiques du positivisme et du néo-positivisme ont progressivement disparu. Sorel soutient, dans le livre que nous présentons, les thèses probabilistes de Boutroux, selon lesquelles dans la sphère scientifique, il fallait toujours passer du dogmatisme positiviste au raisonnement suivant : « passer du nécessaire au probable, passer des mathématiques de la certitude aux mathématiques de l'incertitude" (p. XIV). Pour Sorel, la ligne moderniste en France était née dans le sillage des thèses d'Ernest Renan et du philosophe Eduard Hartmann. Les deux penseurs estimaient que l'affaiblissement dogmatique de la foi conduirait à l'émergence d'une religiosité intérieure plus authentique. Il s'agirait de vivre véritablement l'expérience religieuse, d'en témoigner concrètement dans les actes de la vie. Cela aurait déterminé la réduction du nombre de fidèles, qui se seraient toutefois transformés en authentiques croyants. Sorel, qui proposait aux masses le mythe de la grève générale, a montré, même si c'était avec une certaine ambiguïté, un intérêt sincère pour cette possible religion du futur. À notre avis, il était naïf, les instances modernistes au sein de l'Église, ainsi que dans la société, se sont avérées, en réalité, fonctionnelles au plein déploiement de la Forme-Capital, qui est devenue définitivement mondiale, des décennies plus tard, dans la mythique « révolution » de Soixante-Huit. Puis le Père, symbole de la Loi et de la Tradition, a été assassiné. De son sang est né le royaume de la marchandise absolue, dans lequel nous vivons encore.

Pour Sorel, la ligne moderniste en France était née dans le sillage des thèses d'Ernest Renan et du philosophe Eduard Hartmann. Les deux penseurs estimaient que l'affaiblissement dogmatique de la foi conduirait à l'émergence d'une religiosité intérieure plus authentique. Il s'agirait de vivre véritablement l'expérience religieuse, d'en témoigner concrètement dans les actes de la vie. Cela aurait déterminé la réduction du nombre de fidèles, qui se seraient toutefois transformés en authentiques croyants. Sorel, qui proposait aux masses le mythe de la grève générale, a montré, même si c'était avec une certaine ambiguïté, un intérêt sincère pour cette possible religion du futur. À notre avis, il était naïf, les instances modernistes au sein de l'Église, ainsi que dans la société, se sont avérées, en réalité, fonctionnelles au plein déploiement de la Forme-Capital, qui est devenue définitivement mondiale, des décennies plus tard, dans la mythique « révolution » de Soixante-Huit. Puis le Père, symbole de la Loi et de la Tradition, a été assassiné. De son sang est né le royaume de la marchandise absolue, dans lequel nous vivons encore.

L'État moderne qui est né dans le cadre de l'économie capitaliste libérale s'est soumis à la loi aveugle de l'offre et de la demande comme seul critère de justice, mais ses contradictions et les demandes du peuple, surtout à partir du milieu du XIXe siècle, ont produit un changement qui s'est réalisé à partir de la troisième décennie du XXe siècle.

L'État moderne qui est né dans le cadre de l'économie capitaliste libérale s'est soumis à la loi aveugle de l'offre et de la demande comme seul critère de justice, mais ses contradictions et les demandes du peuple, surtout à partir du milieu du XIXe siècle, ont produit un changement qui s'est réalisé à partir de la troisième décennie du XXe siècle.

Dans le contexte islamique, puisque la révélation y est à la fois prophétie et loi, le sens réel du terme conflit utilisé par Héraclite apparaît avec toute sa force perturbatrice dans le concept théologique de djihad. Cela, rappelons-le, signifie littéralement "effort" et indique l'engagement de l'homme à s'améliorer, à devenir un "vrai" être humain, paraphrasant l'interprétation qu'en donne l'imam Khomeiny [2].

Dans le contexte islamique, puisque la révélation y est à la fois prophétie et loi, le sens réel du terme conflit utilisé par Héraclite apparaît avec toute sa force perturbatrice dans le concept théologique de djihad. Cela, rappelons-le, signifie littéralement "effort" et indique l'engagement de l'homme à s'améliorer, à devenir un "vrai" être humain, paraphrasant l'interprétation qu'en donne l'imam Khomeiny [2].

Dans ce contexte, selon l'historien et homme politique Liang Qichao, qui a vécu au tournant des XIXe et XXe siècles à l'époque du déclin inexorable et de la partition impérialiste de l'espace chinois, la solution ne pouvait être que la création d'une forme de nationalisme chinois. Cependant, ce que Qichao considérait comme du nationalisme était une forme de conscience politique et culturelle nationale, mais pas du nationalisme au sens européen du terme. En fait, ce concept est resté complètement étranger à la forme impériale traditionnelle qui, même aujourd'hui, dans son expression modernisée et influencée par le marxisme-léninisme, ressemble davantage au modèle achéménide qu'à l'idée européenne de l'État-nation et de ses impulsions impérialistes. Et, en tant que telle, elle s'est imposée dès son origine comme un dépassement en nuance de cette idée.

Dans ce contexte, selon l'historien et homme politique Liang Qichao, qui a vécu au tournant des XIXe et XXe siècles à l'époque du déclin inexorable et de la partition impérialiste de l'espace chinois, la solution ne pouvait être que la création d'une forme de nationalisme chinois. Cependant, ce que Qichao considérait comme du nationalisme était une forme de conscience politique et culturelle nationale, mais pas du nationalisme au sens européen du terme. En fait, ce concept est resté complètement étranger à la forme impériale traditionnelle qui, même aujourd'hui, dans son expression modernisée et influencée par le marxisme-léninisme, ressemble davantage au modèle achéménide qu'à l'idée européenne de l'État-nation et de ses impulsions impérialistes. Et, en tant que telle, elle s'est imposée dès son origine comme un dépassement en nuance de cette idée. Ainsi, l'histoire mondiale n'a été que la superstructure historiographique du libéralisme occidental à l'époque de la guerre froide et de l'instant unipolaire.

Ainsi, l'histoire mondiale n'a été que la superstructure historiographique du libéralisme occidental à l'époque de la guerre froide et de l'instant unipolaire. Les États-Unis sont nés dans un "espace libre" où prévalait la loi du plus fort, celle de l'état de nature et sur le fond idéologico-religieux du thème biblique de l'Exode et de la conviction messianique de la construction du "Nouvel Israël" et de la "Jérusalem sur terre" : des principes qui sont à la base de l'idée puritaine de supériorité morale et de prédestination et qui représentent les fondements existentiels de l'américanisme. Les États-Unis sont nés en totale opposition au modèle européen. Leur entrée sur le Vieux Continent marque le passage de la guerre "légale" à la guerre "idéologique" : l'ennemi doit non seulement être vaincu, mais diabolisé, criminalisé et donc anéanti. Ce que les États-Unis ont fait, c'est ramener en Europe la loi du plus fort, en la considérant, comme les Européens l'avaient fait avec l'hémisphère occidental à l'époque moderne, comme un "espace libre" à soumettre à la simple conquête.

Les États-Unis sont nés dans un "espace libre" où prévalait la loi du plus fort, celle de l'état de nature et sur le fond idéologico-religieux du thème biblique de l'Exode et de la conviction messianique de la construction du "Nouvel Israël" et de la "Jérusalem sur terre" : des principes qui sont à la base de l'idée puritaine de supériorité morale et de prédestination et qui représentent les fondements existentiels de l'américanisme. Les États-Unis sont nés en totale opposition au modèle européen. Leur entrée sur le Vieux Continent marque le passage de la guerre "légale" à la guerre "idéologique" : l'ennemi doit non seulement être vaincu, mais diabolisé, criminalisé et donc anéanti. Ce que les États-Unis ont fait, c'est ramener en Europe la loi du plus fort, en la considérant, comme les Européens l'avaient fait avec l'hémisphère occidental à l'époque moderne, comme un "espace libre" à soumettre à la simple conquête.

NOTES

NOTES

La maison d'édition Diana propose la réimpression d'un essai de Marcel Gauchet "Droite/Gauche - histoire d'une dichotomie", enrichi d'une introduction de Marco Tarchi et d'une postface de l'auteur, annexe nécessaire à une publication datant déjà de 1992.

La maison d'édition Diana propose la réimpression d'un essai de Marcel Gauchet "Droite/Gauche - histoire d'une dichotomie", enrichi d'une introduction de Marco Tarchi et d'une postface de l'auteur, annexe nécessaire à une publication datant déjà de 1992. Les finalités, les contenus et les programmes changent mais l'"ordre de bataille" de la politique française reste formellement inchangé : dans un mélange de conflit et de fragmentation, les modérés et les alternances du centre continuent à gouverner, laissant "libre cours" aux doctrinaires des extrêmes et à un dualisme aussi élémentaire que manichéen, virulent et implacable.